Blog Details

who are the 9 gods of Egypt

who are the 9 gods of Egypt

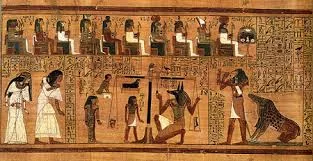

The Ennead of

Egypt

The Ennead of Egypt consists of nine central deities in

ancient Egyptian mythology, forming the core of Heliopolitan theology. These

gods, including Atum, Shu, Tefnut, Geb, Nut, Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys,

are fundamental to the Egyptian creation myths, representing the forces of

nature and cosmic order that shaped their world and belief systems.

Atum, a central figure in the

mythology of ancient Egypt, holds a significant place as the primeval deity

from whom all creation flows. His story is deeply woven into the religious

beliefs and cosmological views of the ancient Egyptians, particularly those of

the city of Heliopolis, where Atum was worshipped as the originator of

existence.

The

Role of Atum in Creation

Atum’s story begins in the vast,

formless void of Nu, the primordial waters that existed before the world. In

this emptiness, Atum emerged as the first being, a self-created entity who

represented the very essence of potential and existence. Unlike other gods who

were often associated with specific elements of nature, Atum embodies the

concept of totality. He is both male and female, the beginning and the end, and

his name itself carries the meaning of "the completed one."

Atum’s act of creation is both

simple and profound. According to the mythology, Atum, in a solitary act of

will, brought forth the first pair of gods, Shu and Tefnut. This act is often

depicted as Atum either spitting or exhaling them from his mouth, symbolizing

the breath of life and the power of speech as creative forces. Shu, the god of

air, and Tefnut, the goddess of moisture, together represent the first differentiation

within the cosmos, giving rise to the fundamental elements that make up the

world.

Atum’s

Symbolism

Atum is often depicted as a human

figure, either in the form of a man or as a serpent, reflecting his connection

to the cycles of life and rebirth. In human form, he is usually shown wearing

the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, signifying his role as a ruler and

unifier of all lands.

The serpent aspect of Atum,

particularly in his association with the evening sun, underscores his

connection to the eternal cycle of day and night, life and death. As the sun

sets, Atum is believed to descend into the underworld, where he takes on the

form of a serpent, only to be reborn each morning as the sun rises again in the

form of Ra, the sun god. This cycle mirrors the journey of the soul through the

afterlife, with Atum playing a vital role in ensuring the continuation of life

and order.

Atum

in the Context of the Ennead

As the head of the Ennead, the group

of nine deities central to Heliopolitan theology, Atum’s influence extends

throughout the pantheon. After creating Shu and Tefnut, these deities, in turn,

gave birth to Geb, the earth, and Nut, the sky. From Geb and Nut came Osiris,

Isis, Set, and Nephthys, completing the Ennead and establishing the divine

family that governs the cosmos.

Atum’s role as the progenitor of the

gods highlights his position as a foundational figure in Egyptian mythology.

His actions set in motion the events that led to the creation of the world and

the establishment of divine order. The Ennead itself is a reflection of the

Egyptian belief in the interconnectedness of all things, with Atum at the

center, symbolizing the unity from which all diversity springs.

The Cult of Atum

.jpeg)

Worship of Atum was deeply rooted in

the religious practices of ancient Egypt, particularly in Heliopolis, where he

was venerated as the original god and the source of all creation. Temples

dedicated to Atum were places of pilgrimage and devotion, where rituals and

offerings were made to honor his creative power and to seek his protection.

The Pharaohs of Egypt often

identified themselves with Atum, invoking his authority to legitimize their

rule and to align themselves with the divine order. This connection between the

king and Atum reinforced the idea that the Pharaoh was a living embodiment of

the gods, responsible for maintaining Ma'at, the principle of cosmic balance

and justice.

Shu, a pivotal deity in ancient

Egyptian mythology, plays a crucial role in the cosmology of the early

civilization. As the god of air and light, Shu is integral to the creation

narrative and the maintenance of order within the universe. His presence in the

pantheon highlights the importance of balance and the separation of the heavens

and the earth, themes central to the Egyptian understanding of the world.

Origins

and Role in Creation

Shu is born from Atum, the primeval

god who self-generated from the chaotic waters of Nu. According to the myth,

Shu was brought into existence through Atum’s breath or a forceful act of

spitting, a symbolic gesture representing the life-giving air. Shu’s twin

sister, Tefnut, the goddess of moisture, was created simultaneously, and

together they represent the first division of elements in the cosmos.

Shu’s primary function in the

creation story is to separate the sky, embodied by his daughter Nut, from the

earth, represented by his son Geb. This separation is a critical moment in the

Egyptian creation myth, as it allows for the formation of the world as the

ancient Egyptians knew it. Shu’s role in holding up Nut above Geb with his arms

stretched out reflects the idea of order triumphing over chaos, preventing the

sky from collapsing onto the earth and ensuring that life can flourish.

Symbolism

and Representation

Shu is typically depicted as a man

wearing a feather on his head, which symbolizes his connection to air. The

feather, a light and delicate object, is a fitting symbol for a deity

associated with the invisible yet vital element of air. In some

representations, Shu is shown with both arms raised, holding up the sky,

reinforcing his role in maintaining the balance between the heavens and the

earth.

As the god of light, Shu is also

linked with the concept of illumination and clarity. His association with light

is not just physical but also metaphorical, representing the power of

revelation and the dispelling of darkness. This dual role as the god of air and

light positions Shu as a protector of life, ensuring that both the breath of

life and the light of day are sustained.

Shu

in the Pantheon

Shu’s significance extends beyond

his role in creation. As one of the earliest deities in the Heliopolitan

Ennead, Shu is a foundational figure in the pantheon. His relationship with

Tefnut, and their children Geb and Nut, forms the basis of the divine family that

governs the cosmos. This family dynamic reflects the interconnectedness of

natural forces, with Shu’s role emphasizing the importance of balance and

harmony in maintaining order.

Shu is also connected to Ma'at, the

concept of truth, balance, and justice that underpinned all aspects of Egyptian

life. By holding up the sky and maintaining the separation between heaven and

earth, Shu ensures that the natural order is preserved, which is essential for

the continuation of life and the protection of Ma'at.

Worship

and Legacy

In ancient Egypt,is khonshu a real god Shu was venerated

as a vital deity, particularly in Heliopolis, where his cult was closely

associated with that of Atum. Temples dedicated to the worship of Shu were

places where rituals were performed to honor his role in sustaining life and

order. The Pharaohs, who were seen as earthly representatives of the gods,

often invoked Shu’s protection and guidance in their quest to maintain Ma'at

throughout the land.

The legacy of Shu endures in the

mythology and religious practices of ancient Egypt, where his role as a

preserver of balance and life was celebrated and revered. His symbolism as the

god who holds up the sky and brings light to the world remains a powerful image

of the importance of harmony and the delicate balance required to sustain life.

Geb, a central deity in the pantheon

of ancient Egypt, holds a significant place as the god of the earth. His

presence in the mythology reflects the ancient Egyptians' deep connection to

the land, agriculture, and the natural cycles that governed their lives. Geb’s

role in the cosmic order and his relationships with other deities underscore

his importance in the Egyptian belief system.

Origins

and Mythological Role

Geb is one of the key figures in the

Heliopolitan Ennead, a group of nine deities that form the core of creation

myths in ancient Egypt. He is the son of Shu, the god of air, and Tefnut, the

goddess of moisture. Geb’s sister and consort, Nut, is the goddess of the sky,

and together they represent the duality of the earth and the heavens.

In the creation myth, Geb and Nut

were initially intertwined, but their father, Shu, was commanded by the sun god

Ra to separate them. This separation allowed for the creation of the world as

it is known, with Geb forming the earth beneath and Nut arching over as the

sky. This myth highlights the essential roles that these deities play in the

structure of the universe.

Symbolism

and Depictions

Geb is often depicted as a man lying

on his side, with one arm bent to support his head, and the other resting on

the earth. His body is sometimes shown covered in green patches, symbolizing

vegetation and fertility, key aspects of his domain as the god of the earth. In

some depictions, Geb is also shown with a goose on his head, which is a reference

to his name, as "Geb" is associated with the Egyptian word for goose.

As the earth god, Geb is

intrinsically linked to fertility, growth, and the sustenance of life. The

ancient Egyptians believed that Geb’s laughter was the source of earthquakes,

and his body was the foundation upon which all life thrived. The soil, crops,

and minerals were seen as gifts from Geb, making him a deity closely connected

to the prosperity of the land and the well-being of the people.

Geb’s Family and Their Influence

Geb’s union with Nut resulted in the

birth of four major deities: Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys. These children

are central to many of the most important myths in Egyptian religion,

particularly the story of Osiris, which involves themes of death, resurrection,

and the eternal cycle of life. Geb’s role as the father of these deities

further cements his importance in the Egyptian mythological framework.

The story of Osiris’s murder by Set

and subsequent resurrection with the help of Isis is a key narrative in which

Geb plays a vital role. As the father of both Osiris and Set, Geb finds himself

in a position of conflict, yet his actions demonstrate his alignment with

justice and order, as he ultimately sides with Horus, the son of Osiris, in the

battle against Set.

Worship

and Cult

Geb was revered throughout ancient

Egypt, especially in regions where agriculture was the backbone of life.

Temples dedicated to Geb, though not as numerous as those of other deities,

were places where offerings were made to ensure the fertility of the land and

the protection of crops. Farmers would often invoke Geb’s favor to bless their

fields and ensure bountiful harvests.

The Pharaohs, seen as earthly

manifestations of divine order, also identified with Geb, who was considered

the physical embodiment of the earth itself. The Pharaoh’s role as a protector

and provider of the land’s wealth resonated with Geb’s qualities, making this

deity an important figure in the religious and political landscape of ancient

Egypt.

Legacy

and Influence

Geb’s influence extends beyond his

role as a god of the earth. His connection to the cycles of life, death, and

rebirth made him a symbol of continuity and stability. The ancient Egyptians

saw in Geb the embodiment of the land’s enduring nature, which outlasts the

fleeting lives of humans and even the reigns of kings.

In funerary contexts, Geb was often

invoked to ensure a safe passage to the afterlife. His association with the

earth also linked him to burial practices, as the deceased were laid to rest in

the ground, returning to Geb, the source of all life.

Nut:

Nut, the goddess of the sky, holds a

profound and essential place in the mythology and religious beliefs of ancient

Egypt. As a celestial deity, Nut represents the sky's vastness and the cosmic order,

encompassing both the heavens and the stars. Her role in the ancient Egyptian

pantheon reflects the culture's deep reverence for the natural world and the

forces that govern the universe.

Origins

and Role in Mythology

Nut is a daughter of Shu, the god of

air, and Tefnut, the goddess of moisture. She is the sister and consort of Geb,

the god of the earth, and together they form a crucial part of the Heliopolitan

creation myth. In this narrative, Nut and Geb were initially entwined in a

close embrace, symbolizing the union of the sky and the earth. However, their

father, Shu, was commanded by Ra, the sun god, to separate them, thus allowing

the creation of the world.

The separation of Nut and Geb is a

pivotal moment in Egyptian cosmology. It is through this act that Nut takes her

place in the sky, arching over the earth and becoming the vault of heaven. Her

body forms the canopy of the heavens, and she is often depicted as a woman

stretched across the sky, with her fingers and toes touching the horizon. The

stars and heavenly bodies are believed to be embedded in her body, and she is

responsible for the daily cycle of the sun and the night sky.

Symbolism

and Representation

Nut's imagery is both powerful and

evocative. She is often depicted in ancient Egyptian art as a slender woman

with a starry body, stretching across the heavens. Her skin is sometimes shown

in a deep blue color, symbolizing the night sky, or covered in golden stars,

representing the celestial bodies. Nut's posture, arched over the earth,

emphasizes her role as a protective and nurturing force, enclosing and

safeguarding the world beneath her.

In some depictions, Nut is shown

swallowing the sun in the evening and giving birth to it again each morning.

This cycle represents the daily passage of the sun and underscores Nut's

connection to the rhythm of time and the natural order. Her role as the mother

of the sun god Ra further cements her importance in the Egyptian understanding

of the universe's workings.

Nut’s

Family and Their Impact

Nut’s union with Geb produced four

significant deities: Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys. These children are

central figures in many of the most important myths in Egyptian religion,

particularly the story of Osiris, which deals with themes of life, death, and resurrection.

Nut’s role as the mother of these gods highlights her position as a progenitor

of the divine and underscores her connection to the cycle of life and death.

The relationship between Nut and Geb

also reflects the ancient Egyptian understanding of the natural world. While

Nut represents the sky and all that is above, Geb symbolizes the earth and all

that lies below. Their separation by Shu is seen as a necessary division that

allows life to exist and flourish within the space between them.

Worship

and Cult

Nut was revered across ancient

Egypt, particularly in her role as the goddess who provides the night sky and

ensures the sun’s rebirth each day. Temples and shrines dedicated to Nut were

often places where rituals were performed to honor her protective nature and to

ensure the continuity of the natural cycles she governed.

As a deity associated with the sky

and the afterlife, Nut played a crucial role in funerary practices. The ancient

Egyptians believed that the souls of the deceased would ascend to the sky and

reside among the stars, which were considered the children of Nut. Coffins were

often decorated with images of Nut, and she was invoked to protect and guide

the dead on their journey to the afterlife.

Legacy

and Influence

Nut’s influence extends beyond her

role as a goddess of the sky. Her connection to the cosmic order and the

natural cycles of life and death made her a symbol of protection and

continuity. The reverence for Nut in ancient Egypt Luxor by bus from hurghada reflects a broader cultural

understanding of the importance of the heavens and the forces that govern the

universe.

In art and literature, Nut continued

to be a prominent figure, symbolizing the nurturing and protective aspects of

the divine. Her imagery as the arching sky goddess remains one of the most

enduring symbols of ancient Egyptian religion, representing the unbreakable

connection between the cosmos and the earth.

Osiris:

Osiris, a prominent figure in the pantheon of ancient Egypt,

was revered as the deity associated with the afterlife, fertility, and

resurrection. His narrative is deeply intertwined with themes of death and

renewal. According to legend, Osiris was betrayed and dismembered by his

brother Set, only to be reassembled and revived by his devoted wife, Isis. This

resurrection not only solidified his role as the ruler of the underworld but

also symbolized the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth, a concept

central to Egyptian spirituality. Osiris was often depicted as a mummified

figure, reflecting his connection to the eternal and the transformative power

of death, guiding souls to the afterlife and ensuring their journey to the

realm beyond. His influence permeated Egyptian culture, shaping their

understanding of mortality and the promise of life beyond the grave.

Isis:

Isis, a central figure in the religious traditions of

ancient Egypt, was venerated as the embodiment of motherly devotion, magic, and

healing. Her story is marked by her unwavering dedication to her husband,

Osiris, whom she restored to life after his untimely demise at the hands of

Set. This act of restoration not only made her a symbol of loyalty and love but

also highlighted her powers over the mystical and the unseen. Isis was often

portrayed with outstretched wings, symbolizing protection and the sheltering

nature of her care. She played a key role in guiding and nurturing her son,

Horus, ensuring his eventual triumph over Set, which restored balance to the

cosmos. The influence of Isis extended far beyond the borders of Egypt, with

her worship spreading across the ancient world, where she was revered as a

powerful protector and a source of wisdom and renewal.

Seth:

Seth, a complex and often controversial figure in the

mythological landscape of ancient Egypt, was associated with chaos, storms, and

the untamed forces of nature. His character is most famously known for his

rivalry with his brother Osiris, whom he overthrew in a violent struggle for

power. This act of fratricide marked Seth as a symbol of disorder and upheaval,

embodying the darker aspects of existence. However, his role was not entirely

negative; in some narratives, Seth was also seen as a necessary force, one who

challenged and brought balance to the natural world. He was often depicted with

a unique, enigmatic animal head, representing his connection to wild,

unpredictable elements. Despite his fearsome reputation, Seth’s presence was

crucial in the pantheon, as he personified the inevitable disruptions that are

part of life’s cycles, reminding the Egyptians of the duality of existence.

Nephthys:

Nephthys, a lesser-known yet significant deity in ancient Egyptian lore, was closely linked to the themes of mourning, protection, and the boundary between life and death. Sister to Isis and wife to Seth, she played a pivotal role in the mythological drama surrounding Osiris, often acting as a silent but powerful force in the background. Nephthys was seen as a guardian of the deceased, offering comfort and solace to those making the journey to the afterlife. Her presence was essential in rituals of passage, where she, alongside Isis, would prepare the dead for their transition to the next world. Though her stories are often overshadowed by those of her more famous relatives, Nephthys’s influence was deeply felt in the sacred traditions of Egypt, where she symbolized the protective embrace that guided souls through the unknown, embodying the quiet strength found in the shadows.